Niyog was an ancient practice of begetting a child from someone other than one’s husband, especially when the latter was unequipped. Effectively, this meant that if the husband was impotent, then the wife, with the permission or the knowledge of her husband (and/or her family members) could allow some other male (often from the same family) to beget a child onto her. The child would be known as the child of the husband and the niyog partner would never be mentioned. A woman was seen as a field and it was the man’s responsibility to plant his seeds in the field and he was thus the owner of the harvest. So there were sperm donors in ancient times.

This was probably the ancient alternative to modern artificial methods of conception, except that in the case of niyog, there was physical contact between the donor and the wife.

Related reading: Mahabharata’s Bhima may have married the most modern woman ever. Find out who!

The epic Mahabharata deals with this subject at great length and over two generations, once when Satyavati calls for niyog for the widows of her son, and the next is when King Pandu seeks ‘divine’ intervention for his wives Kunti and Madri.

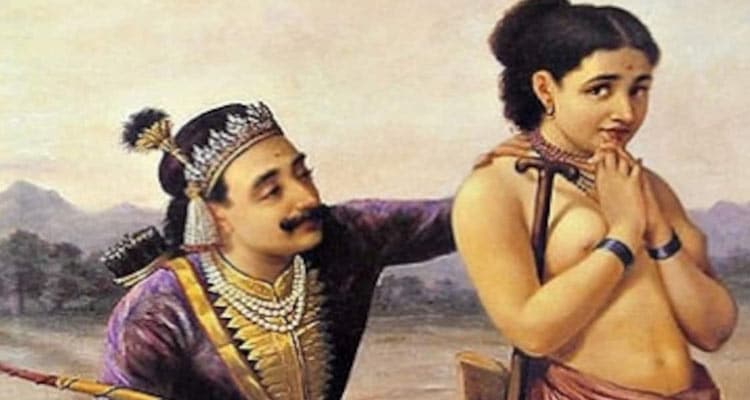

Satyavati and Vyasa

Table of Contents

When Satyavati’s son Vichitravirya died without leaving an heir to the throne of Hastinapur, niyog was resorted to. However, certain norms seem to have been subverted in this case. Niyog was performed after the death of the husband, and thus without his knowledge, but with that of his mother, Satyavati, the queen-mother. Also, niyog must be performed by the husband’s brother, and in this case, Bhishma declined to participate, as he had sworn celibacy. So sage Vyasa was called, Satyavati’s son from a relationship before her marriage to King Shantanu, and thus not directly from the same family, at least not the paternal side. Was there no other option?

King Shantanu had an elder brother by the name of Vahlika and his son Somadatta could have been an ideal choice. But then this could lead to political complications. Vahlika had inherited their maternal grandfather’s kingdom, while Shantanu became the king of Hastinapur. To invite one of Vahlika’s sons could only complicate matters for the ownership of the kingdom in the future. So after Bhishma declined, the next safe bet was Vyasa, thus heralding the additional option of Brahmins getting into the act. There even existed a separate class of Brahmins, known as the Niyogi Brahmins!

Niyog and miraculous birth conceptions

The sole purpose of niyog was to beget a child, and often the two involved in niyog wouldn’t even meet or mention the act. Lust and sexual pleasure weren’t supposed to be objectives and one of the rules laid down by the scriptures was that the male should smear himself with ghee, to ensure that he was unattractive enough during the act.

Related reading: What mythology says about who enjoys sex more

However, Vyasa is upset with the responses of both Ambika and Ambalika and curses their children before their birth (she who closed her eyes had a blind son and she who flinched away had an albino child), and when pleased with the maid, who was sent third, he blesses her with a healthy and intelligent child.

Kunti and her partners

In the next generation, once again, there seems to be a problem. Pandu could not father children on his two wives Kunti and Madri. Once they leave the confines of the palace for the foothills of the Himalayas, Kunti invokes the gods (Dharma, Vayu and Indra) to beget children on her. However, according to Iravati Karve in Yuganta, Dharma (Yama) was a strange choice to be invoked as the first god for conception. Vidura was an incarnation of Yama and his love and concern for Yudhishtir hasn’t quite been hidden in the epic. Could it be that for the conception of a child, Vidura was called and not Yama? Besides, Vidura was also the right choice, given the rules of niyog, as the younger brother of Pandu.

Why does the epic have to hide this fact, when it doesn’t hide any other secrets? Karve believes that Vidura was kept away from the throne because of his lesser-born (daasi-putra) status and if Yudhishtir’s parentage was linked to Vidura, his claim to the throne would be jeopardised too. Since the sons were born in the Himalayas and that too during Pandu’s lifetime, the question of parentage wasn’t raised, though we do find Duryodhan often challenging the legality of the Pandavs’ claim to being the sons of Pandu.

Sperm donors and Niyog were not an Indian concept only

The principle of Niyog wasn’t limited to ancient India only. The Jews followed a similar practice, levirate. However, in levirate, the husband’s brother had to marry the widow of his brother before the act.

Niyog had the ‘need’ of a male child by any means as its root cause. Society ensured that a man who was unable to father children for natural reasons didn’t die childless. The matter was kept within the family and if none were available within the family, then one could seek help from the Niyogi Brahmins for the purpose. While the need was relatively simple, such practices gave rise to complications of sexual politics! That’s a story for another time.

Ask Our Expert

You must be Logged in to ask a question.

Featured

7 Signs Someone Is Constantly Thinking About You – It’s More Than Just Coincidence

Seeing 222 When Thinking Of Someone – Meanings And What To Do

Your Guide On Numerology Compatibility – What’s Your Life Path Number And Who Are You Most Compatible With?

Twin Flame Reunion – Clear Signs And Stages

Psychic Expert Shares 21 Spiritual Signs Your Ex Misses You And Wants You Back

What Is The Spiritual Meaning Of Being Pregnant In A Dream? 7 Possible Explanations

17 Powerful Signs From The Universe Your Ex Is Coming Back

What Is Agape Love And Its Role In Modern Relationships

Sexual Ties: Meaning, Signs, And Tips To Break Away

21 Miraculous Prayers For Marriage Restoration

Psychic Expert Shares 11 Spiritual Signs He Will Come Back

List Of Angel Numbers For Love And Relationship

10 Signs You Are In A Spiritual Relationship With Someone

11 Beautiful Ways God Leads You To Your Spouse

What Does Yin And Yang Mean And How To Find The Balance

Everyday Yin And Yang Examples In Relationships

8 Types Of Soulmates And Deep Soul Connection Signs

Cosmic Connection — You Don’t Meet These 9 People By Accident

21 Beautiful Prayers For Your Husband For Everlasting Love

In Mahabharata Vidura Was Always Right But He Never Got His Due